The explosion in indie game distribution has been both a godsend as well as a curse. We have access to a greater variety of games, sure, but also that means there is a lot of shit out there. Don’t get me wrong – I’m happy that more people are getting interested in game design. But some people just don’t belong in the world. The team at The Fullbright Company definitely deserve a space within the indie development world, and that’s thanks to their wonderful game Gone Home.

The genre Gone Home exists in is technically labeled as “interactive fiction” – a broad term that basically means you don’t kill anything or play any sports. All video games are interactive fiction, but many who attempt to do what Gone Home has done fail miserably. Honestly, it’s probably due to the skillset of the developers and designers. The creators at The Fullbright Company are technically skilled – they previously worked on some DLC for BioShock 2 – but they also bring a certain prowess in the storytelling department that is missing from most titles, from AAA to shoestring budgets. This ends up being the differentiating characteristic for Gone Home: the story and gameplay support each other perfectly. No sacrifice.

The game centers around your character, Katie, coming home from an extended absence. Expectations of family greetings and branching dialogue trees are abandoned immediately when you find the estate is free of any other character. This is a rejection of the typical structure of video games, where storytelling has always relied on exposition from key NPCs to move the plot forward. Here, the only thing moving you forward is a note on the door from your sister, Sam, telling you in a vague manner not to worry about her. Did she runaway? Is she hanging from the rafters somewhere in the house? Was she murdered and the murderer still at large in one of the many dark rooms? These are the questions that Gone Home has you asking within the first thirty seconds of gameplay. In a day and age where so many experiences are profiled and spoonfed, it is refreshing to see a game’s momentum dictated by a player’s desire for an answer.

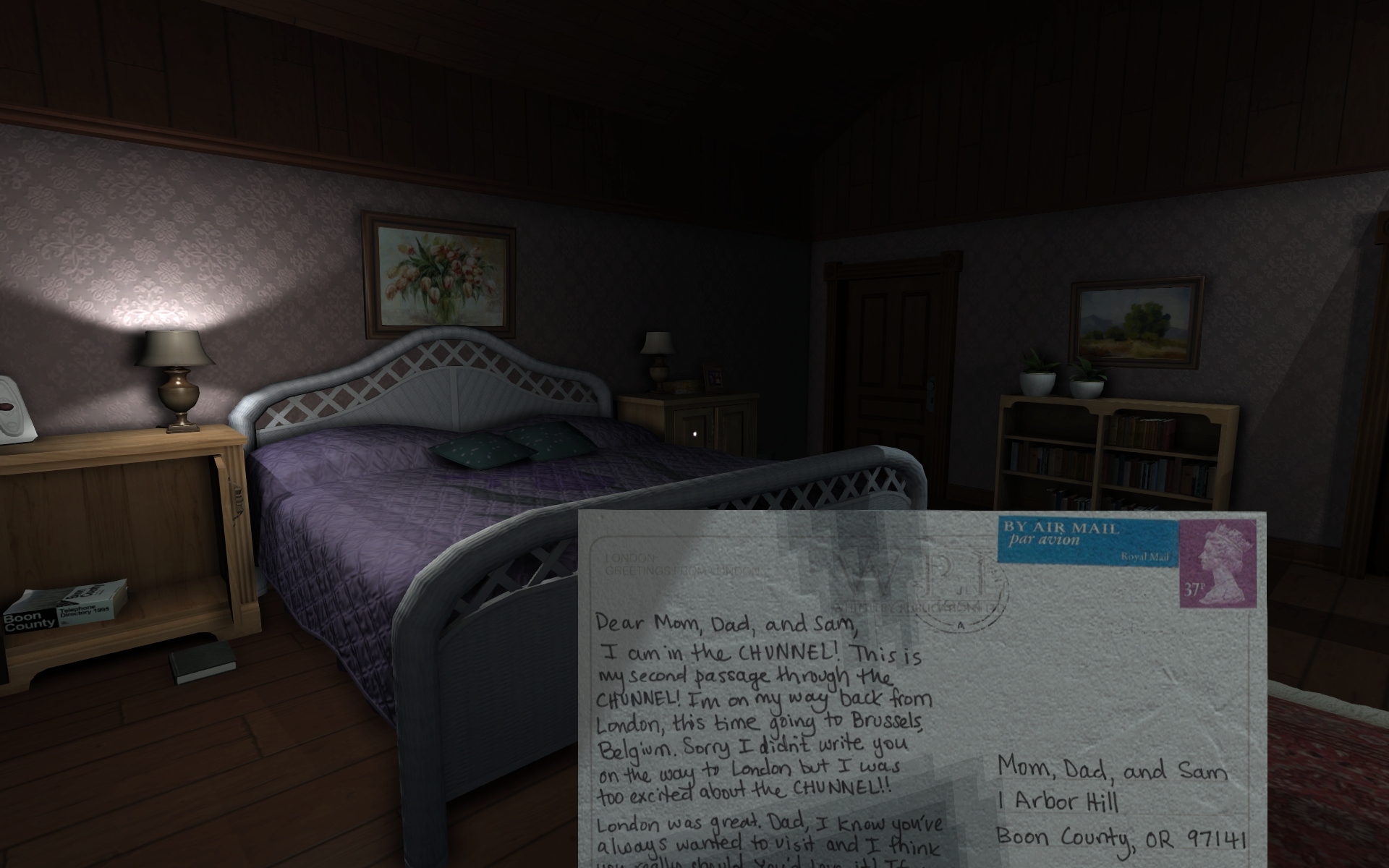

The house may be free of human beings, but it is filled to the brim with objects. The goal is to find out where you left off and what that cryptic note from your sister actually means by way of picking the house apart. It’s the only action you have at your disposal, but that’s a fresh departure from overly-complicated inventory systems. Reinforcing this pathway is the 1995 setting of the game – everything is period accurate, even the simpler gameplay adheres to this restriction. As you slowly make your way through the dark house, and as you inspect each item closely, you begin to put the puzzle together in your mind. Not only are you discovering what happened to your family members, but also who you were. Are you what’s in the bags on the front porch or the plaques celebrating your success on the family’s bookshelves?

The experience of playing Gone Home is what differentiates it from the pack. At one point in my exploration, I came upon a romance novel with a hunky male firefighter on the cover, standing in front of a raging forest blaze. I thought back to my in-game mother’s occupation in forestry. I also recalled the memo about a new transfer to her department, and the glowing words she wrote advocating for permanent placement. I returned to the note and saw that it was a man. That’s how quickly it happens. At one point, I’m playing a cassette filled with punk songs to uncover my little sister’s whereabouts and I began to think my mother is having an affair. That moment for me was a revelation and I was putty in the hands of the designers.

Gone Home is not without its flaws though. The biggest stumbling point was the manipulation system of objects. Sometimes it worked really well, and other times it was buggy. Some items could be rotated, others could not. I had greater difficulty when I tried the game on a laptop – manipulating objects was often a frustrating endeavor. I would level that the only issue I had with the storytelling was that Sam’s friend Lonnie, who plays a significant part in the tale, wasn’t fleshed out as well as the other characters. Her fingerprints are on the house, but I didn’t get to know this intriguing person. Maybe that will be in Gone Home 2?

Gone Home should be a mandatory play for all new developers and designers. It does so many things right in terms of story that it should be the standard for video game plot progression going forward. The gameplay is informed by the plot, not the other way around. Limitations are recognized and avoid, while strengths are given center state. It’s the difference between Candy Crush Saga and Citizen Kane. I’m hoping that Gone Home influences and spawns a new host of adventure games, though you’re going to be hard pressed to find someone who can execute a simple story like this with such deftness.